Do I need antibiotics for a sinus infection?

Sinusitis is a common upper respiratory illness with over 30 million adults in the U.S. diagnosed annually.1 Sinusitis accounts for more than 1 in 5 antibiotic prescriptions for adults, making it the fifth most common diagnosis responsible for antibiotic use and resulting in $5.8 billion in annual healthcare costs.

Sinusitis also known as rhinosinusitis is an inflammation of the mucosal lining of the nasal passage and paranasal sinuses.3 Usually with symptoms of headache, ear pain and thick nasal drainage. Symptoms typically come on very slowly and when lasting less than 4 weeks can be classified as acute, 4-12 weeks subacute, and more than 12 weeks chronic. The between acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) and viral rhinosinusitis is sometimes a challenge for the patient and the providers. . Acute rhinosinusitis usually begins after an upper respiratory infection (URI), then inflammation moves into the paranasal sinuses. It is estimated that 90%-98% of acute rhinosinusitis cases are viral, whereas only 2%-10% of cases can be attributed to bacterial causes.3

Unnecessary use of antibiotics for viral sinusitis exposes patients to preventable and potentially serious health problems. The most severe is the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria. This is a critical public health threat with a reported 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occurring each year and claiming the lives of 35,000 people in the U.S. each year.4 The CDC estimates that up to 30% of all antibiotics prescribed in the outpatient setting are unnecessary.5 Urgent care providers have the highest percentage of visits leading to an antibiotic prescription . Urgent care centers were much more likely to prescribe antibiotics unnecessarily for respiratory illnesses that don’t require antibiotics.2

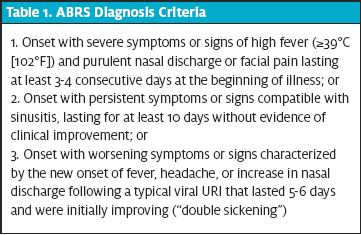

The current guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of sinusitis were developed by the Infectious Disease Society of America and American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery.1,3 They include things like onset, duration, and whether the symptoms seem to be improving. These help the provider decide whether the infection is acute, or chronic and whether the infection is viral or bacterial.(table1) Treatment for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis consist of antibiotics that fall into several categories. Augmentin which is considered first-line treatment for non-penicillin allergic patients is considered a b-lactam. The macrolides include azithromycin (zpack) and clarithromycin. Other categories include the respiratory quinolones (moxifloxacin and levofloxacin) are also options but are not superior to amoxicillin-clavulanate and carry a higher prevalence of adverse effects and increased costs. Other than antibiotics measures that could be recommended for both ABRS and viral sinusitis include acetaminophen and motrin, intranasal saline irrigation, intranasal corticosteroids, oral steroids and hydration. Topical and oral decongestants or antihistamines are typically not recommended as supportive care treatments due to low efficacy.

It is vital for providers to ensure that quality is not sacrificed for convenience in this fast-paced setting. Given the global threat of rising antibiotic resistance, rigorous antibiotic stewardship is becoming increasingly important. A reduction in antibiotic prescribing for acute rhinosinusitis shows the value of a simple educational intervention for providers coupled with an algorithmic CDS tool. This is a promising approach that could be easily implemented in urgent care and other ambulatory settings with a similar method. Future directions could include patient education about viral illnesses and adjustment of patient expectations.

References

- Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): Adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 2015;152(2 Suppl), S1-S39.

- Palms DL, Hicks LA, Bartoces M, et al. Comparison of antibiotic prescribing in retail clinics, urgent care centers, emergency departments, and traditional ambulatory care settings in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. 178(9):1267-1269.

- Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012. 54(8):e72-e112.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States: 2019.Availablet at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf. Accessed Ocober 5, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic use in the United States, 2018: Progress and opportunities. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/pdf/stewardship-report-2018-508.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- Pulia M, Redwood R, May L. Antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018;36(4):853-872.

- Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 2018.